(For HD viewing you can click to the Vimeo website)

The Project

Digital Dwelling at Skara Brae is a collaborative project bringing together three visualisation specialists, each with very diverse methods and mediums of working. The project was initiated following a series of discussions between PhD researchers Alice Watterson and Kieran Baxter together with Dr Aaron Watson, which established a mutual concern for the ways digital methods were shaping archaeologists’ engagement with sites and material culture.

While field archaeologists engage with the archaeological record through their senses, these experiences are often mediated through technologies such as cameras, survey machines or scanners. This influences and even constrains the kinds of information that is observed and recorded, effectively distancing the field worker from their material. Through the act of making an experimental film the project explores the potential of layered multimedia as an archaeological field method; capturing and communicating very different qualities of the archaeological record to systematic and objective techniques of data collection alone.

As a work in progress, the film moves from the present day to the imagined past; from a remote aerial perspective to an embodied encounter deep within the walls of the village; and from objective interpretation to creative storytelling.

Survey

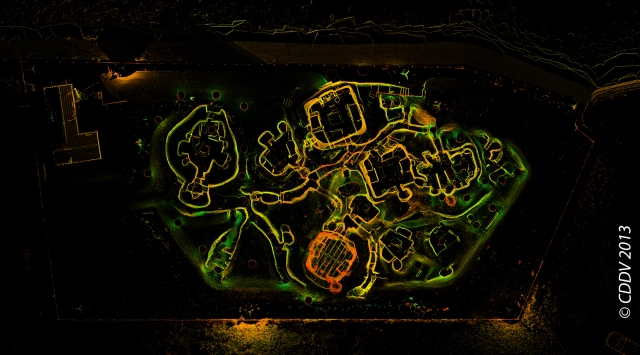

The Neolithic site of Skara Brae, located in Mainland Orkney off the northern coast of Scotland, was surveyed in 2010 by the Scottish Ten project using laser scanners and photogrammetry rigs.

Method

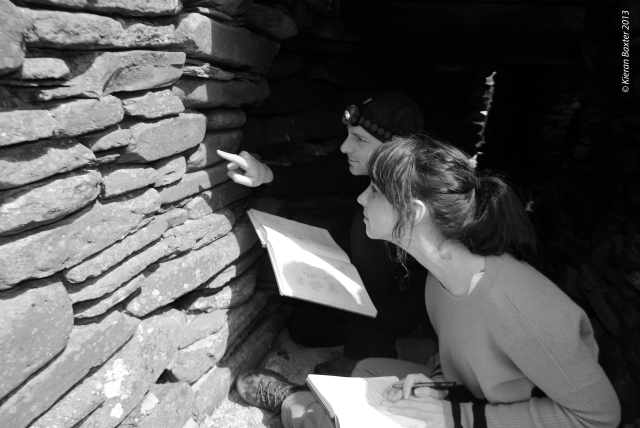

The fieldwork combined site visits to both Skara Brae and contemporary sites within the wider landscape with laser scanning, photogrammetry, kite photography, film, painting and drawing. We made a conscious effort to engage with the site through our creative process with an awareness of acoustics, texture, and the experience of moving through the space. Adoption of a more involved way of recording a site gave us time to linger, observe and interpret.

A Disembodied Perspective

Kite aerial photography was incorporated into our observations at Skara Brae in an attempt to summarise the complexity of the site in a single overview.

From the oblique angle chosen for this shot, the features within Skara Brae are separated out whilst remaining recognisable, helping the viewer to orientate themselves and establishing the site within its immediate landscape. There is also a dichotomy accompanying this aerial imagery, which is at once familiar and estranged. In contrast to the elevated view from the sea cliffs, this suspended view departs from the experience available to fieldworkers, visitors, or people in the past.

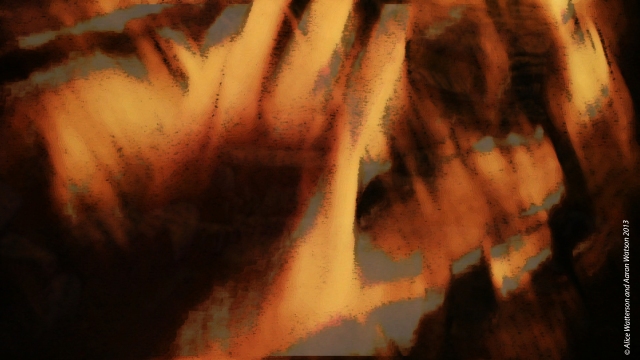

Scratch Art and Boundaries

In the film the camera moves down into a passageway then turns to focus upon a stone incised with abstract lines which are lit by flickering red firelight dancing across the surface. In this sequence, live action footage is mixed with computer generated shots of Neolithic art.

Scratch art within the passageways appears at apparent spatial boundary points and has been described as being ‘muted’ and ‘secretive’ (Shepherd 2000), implying that its meaning is more than decorative. Our film acknowledges this incised art as the camera lingers across the stone surface, while abstracted shapes evoke memories or visions.

An Embodied Perspective

The camera turns sharply and enters a low and foreboding passageway. Erratic movement reinforces the sense that we are now looking through the eyes of a protagonist. Hands reach out to guide through the darkness and then the image distorts, suggesting visions or memories evoked within this confined place.

Passage B is an uncomfortable and claustrophobic place, requiring the visitor to crawl around a tight corner and down a slope. We included shots of our hands to directly capture the difficulties of negotiating this space, reinforcing the impression that the protagonist/audience are now situated firmly within the scene; that this is now an embodied experience.

Transformation

The camera then moves through a narrow entrance, revealing the interior of a dwelling and a figure dimly visible through the smoky atmosphere. The figure is holding a ceremonial artefact – a Neolithic carved stone ball – and during the conclusion of this transformative encounter this is handed to the protagonist.

In this scene the interior of House 7 is a computer model created from laser scan mesh and texture data. Reconstructed elements were then digitally modelled, including the speculative architecture of the roof, artefacts, a costumed character, lighting and atmospheres. The shot of the incised art combines sequences of animated photogrammetry captured in the field and draped with a painted image.

There is evidence to suggest that House 7 was treated differently to other dwellings in the village. It is spatially separated by the uncomfortable crawl down Passage B and two female burials were placed under the right hand bed when the foundations of the house were laid. It is also the only structure which has a door that can be locked from the outside (Richards 1991). These unusual qualities inspired us to convey this space as a convergence of domestic and ritual. The camera is hesitant, suggesting unfamiliarity or caution on the part of the protagonist, and the unexpected appearance of shifting imagery and colour conveys further ambiguity or strangeness, and is also suggestive of the altered states of consciousness often associated with ritual.

Digital Dwelling

With creative work like this it would be easy to create a fiction about the site, but we don’t because we are bound by the archaeological record. We work within the space interpretation can occupy while still responding to the evidence.

The narrative arc of the film is driven by a convergence of evidence from the archaeological record and our own sensory engagement as field workers; from the virtual to the actual, and from the sky to the underground. The journey begins with the disembodied perspective of flight, and ends with a direct encounter with an imagined person; from the wider landscape to a single artefact. The film is not a reconstruction as this would suggest that it is possible to see through the eyes of Neolithic people. Instead, it is a story about our own engagement with the archaeological record at Skara Brae. It portrays the past as it is experienced in the present; unfamiliar, emotive, dynamic and transforming.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Historic Scotland for funding this project and to the Scottish Ten team and CDDV (Centre for Digital Documentation and Visualisation) for provision of data. Thanks to both the Digital Design Studio at the Glasgow School of Art and to the Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, The University of Dundee. We are especially grateful to Alice Lyall and Stephen Watt for arranging site access, and also to Mary Dunnett, Ann Marwick, Alan Jones and staff at Skara Brae and Maeshowe. Special thanks to Nick Card, Jane Downes, Caroline Wickham-Jones, Antonia Thomas, Peter Needham, Neil Firth and all those who took part in a focus group hosted by Orkney College. Kit Reid and Richard Strachan for their support and feedback. Alastair Rawlinson for his wisdom and assistance back in the lab. Finally, thanks to Jeremy Huggett and Paul Chapman for their advice and guidance.

Reblogged this on Visualising Neolithic Orkney.

Nice work Alice. The video looks really cool and the discussion of the work is very interesting.

Thanks Jon 🙂

WOW that really was intense accidentally had my sound turned right up… But I really felt like I was engaging with the neolithic especially when you enter the room with the woman sat by the fire! I look forward to seeing the feature length version 🙂

This is great stuff – I run a forum for digital archaeologists (https://plus.google.com/u/0/communities/111025777646931985833) – we’d love to have you along.

Henry

Thanks Henry! I’ve signed up to your forum!

What an inspiring film! Great use of past, present and future connections- brilliant way to bring the present into the past.

Thanks for bringing another dimension to a world class site.

Thanks everyone, really glad you’re enjoying the film! Hopefully it’s serving its purpose to challenge the often passive consumption of reconstruction images and engaging people with the interpretation 🙂 something a bit different anyway!

Terrific film. I applaud the way you’ve created something evocative and emotional while staying true to the evidence. Great interpretive work.

This is truly amazing – you’re so talented! 🙂

Reblogged this on Graham Edwards and commented:

Last year I spent some time researching the Scottish neolithic settlement of Skara Brae for a new novel. I wish I’d found this amazing blog then. Still, better late than never. This is a great example of interpretive archeology, with a particularly impressive short film presenting the ancient village environment as an immersive, sensory experience. The aerial photography (shot from a kite) is terrific.

[…] Online Exhibition: Digital Dwelling at Skara Brae (digitaldirtvirtualpasts.wordpress.com) […]

[…] Digital Dwelling at Skara Brae (visualisation/interpretation video project) […]

A reblogué ceci sur Digital Draw Archaeology and commented:

The ideas of your blog are very good, i like your “digital idea” of the archaeology.

I’m not an archaeologist. I’m just an inquisitive member of the public with a strong interest in archaeology. Skara Brae’s value to understanding humans just doesn’t fit into words. As a member of the Great Unwashed, I was very disappointed by the video. I’m disabled. I’ll never get to Skara Brae in person. My best way of understanding it would be a virtual tour and your video is a fantastic idea but I found this one to be frustrating to the point of distaste. I know I’m being harsh, but for me, the “interpretive” elements were just annoying. There’s only one Skara Brae, but nearly every person on the planet has two hands. Most of us see hands all day long, every day. The hands were just annoying and a waste of video time.

And it seems unfair to “interpret” the site for us. I could tell, from the little I could see of the passageway, that it was cramped and disorienting. But some of us might not get disoriented that easily. Obviously the inhabitants of Skara Brae didn’t have a problem with it. So how is it right to waste precious video time imposing someone’s interpretation of the site on all viewers? Instead of coming away with more of an understanding of how I feel about Skara Brae, I’ve sat through six minutes of someone trying to tell me how to feel about it.

And the interpretation isn’t even that good. The house contained a modern hatchet. The person by the fire could have been doing something useful like using a drop spindle. Drop spindles are easy to learn to use, dead easy to fake using and you can bung up a good fake in less than sixty seconds. And why would you paint a house in *bright* colors if the interior is only lit by firelight?

I know a lot of work went into making this video and I know the intentions were good so I feel bad about being so harsh but I’m a member of the target audience. I’m not an academic. I’m not a film maker. I’m an interested everyperson who treasures human heritage and wants to understand us better and this video just didn’t help with that for me.

Hi Ingrid, sorry you didn’t like the film though hopefully if I explain a bit about how it came to be made you’ll see why the video is as it is.

Rather confusingly for something which has ended up in the public eye the film was never made with a specific target audience in mind. The research I was doing at the time investigated the ways in which different archaeological visualisation techniques (from scientific and objective to creative and subjective) could be layered together within one single output. The purpose of the film then, rather than to produce something specifically for public outreach, was to use the fieldwork time as an experiment in collaborative working between myself and a group of specialists working with different techniques and interpretive intentions. So instead of working towards a final known goal, the film is a product of this experimental fieldwork process.

In directing the project I allowed the team to freely explore their developing relationship with the site through their own techniques and a personal response was actively encouraged. In this sense you’re bang on when you imply that it’s one singular personal interpretation of the site – it absolutely is and that was intentional. We consciously chose to engage with our personal experience in interpreting the site because I wanted to emphasise the fact that all archaeological visualisation represents the past in the present – this can’t be avoided and it’s a fundamental part of the work of a reconstruction artist so why not convey it within the film? When you consider this, all interpretive visualisation within archaeology on some level is the product of the personal interpretation of a small group of people communicating their view to the masses. Some choose to represent this process as a scientific one, we chose to emphasise its subjectivity and ambiguity.

To address a few of the specific points within your comment: with regard to the ‘over-use’ of hands within the film, you say that everybody on the planet has two hands – exactly! As my colleague Aaron pointed out to Kieran and I during the fieldwork, if you roll up your sleeve you have a Neolithic hand, it’s instantly relatable. We made use of hands within the film first to make the viewer feels as though they were becoming more embodied within the story as they scrabbled down the narrow passageway. Compared to the rest of the village architecture the passage leading to hut 7 is particularly cramped and slopes downhill. No doubt the Neolithic inhabitants would have become fairly nifty at negotiating this passageway – but to the modern visitor it’s a tight and uncomfortable squeeze and we wanted to convey that to the viewer.

The painted hands towards the end of the film were used to draw attention to the tactile nature of the carved stone artefact the woman is holding and also to make a direct and very human connection with the protagonist as the artefact is handed over. The hands and scratch art were painted brightly in the film not as a direct interpretation of the evidence (though we do know some people in the Neolithic were painting their scratch art with natural ochre pigments) but from the interpretive perspective of an artist in the present day. Aaron’s bright vivid colours and abstracted shapes were his way of engaging with the evidence and re-imagining it through his own work.

In terms of having the character in the house engaged in a specific activity, the list of possibilities could have been endless, but we made a decision to emphasise the more intangible and ritualistic elements of the evidence from Hut 7, which seems to have been treated very differently to the other dwellings within the village. Due to the complex nature of interpreting ritual and belief systems in prehistory the majority of representations of archaeological sites tend to focus on the domestic alone. As there are already a multitude of reconstruction type images dealing with domestic life at Skara Brae we thought we’d supplement what interpretive materials were already available by approaching our representation from a different perspective. And in many ways that’s the beauty of archaeological visualisation – different images can address different areas of the interpretation of the site. The real world and the archaeological record are so vastly complex that it’s near impossible to recreate and represent every aspect of life on the site so, as with all the reconstruction work I do, I have to decide what elements to show and what to leave for another visualisation. What makes the cut has to tie in with the rest of the narrative, and in this case we wanted a continuation of the strangeness and uncertainty represented within Hut 7, so placing a ritual/meditative object in the painted hands seemed more appropriate to the story we were telling than if the hands had been engaged in a domestic activity.

You’re completely right about the axe – I placed a model of a hatchet I already had in the scene as a ‘place-holder’ when I was dressing the interior of the reconstruction, meaning to switch it out when I had time to model an authentic Neolithic axe. Unfortunately with the panic of finalising the animation in time I forgot to switch it out and sent the animation off to process. Each frame within the animation took about 45 minutes to process or ‘render’ and there are 25 frames per second so you can imagine how long that takes! After about 3 and a half weeks of the animation segments rendering out , by the time I noticed the mistake it was too late to start the process over. You’ll notice in the stills which accompany the post the hatchet has been replaced by an axe. Totally my fault, but such is the nature of student film-making!

Hopefully that’s gone some way to addressing your feelings on the film, at the end of the day it was a student production made to explore fieldwork process and storytelling techniques rather than something which was intended to be shown to various audiences as it has been – for instance it really has to be viewed with the accompanying exhibition content explaining the intentions behind the project otherwise it makes very little sense! If I was to direct the film again I’d do a lot of things differently. Once we’d completed work on the film Historic Scotland were keen for us to show it on site and everything just took off from there. If it had been intended from the offset to be shown in a public context it would have had some type of audio narration or subtitles, and the themes we addressed would have been tightened up and made far more visually coherent.

At the end of the day the film was an experiment and the product of a creative, messy, unpredictable and incredibly revealing learning process. It was tremendously illuminating to the research I was doing at the time and really helped me to learn about the ways other specialists and artists approached the task of interpreting and representing a hugely complex site. It isn’t perfect but it did the job for my research and certainly generated a lot of discussion about interpretation of the site!

If you fancy a laugh you might enjoy the mock-up poster I made to accompany this blog post – https://digitaldirtvirtualpasts.wordpress.com/2014/01/09/and-the-reviews-are-in-evaluating-digital-dwelling/

Best, Alice

[…] https://digitaldirtvirtualpasts.wordpress.com/2013/05/26/online-exhibition-digital-dwelling-at-skara… […]